Bias #24: Loss Aversion, 3-minute read

Defined:

Loss Aversion: People would rather avoid a loss than gain an equivalent reward.

Described:

Will you take this bet: I’ll flip a coin—if it’s heads, you lose $100, but if it’s tails, you win $100?

Most people decline. But why? The odds are equal (50/50) and so are the stakes ($100/$100). Someone who experiences gains and losses equally would have said yes.

How about this: heads, you lose $100; tails, you win $200?

Ah, now we’re talking. Most people take the second bet because the reward for winning is twice the penalty of losing.

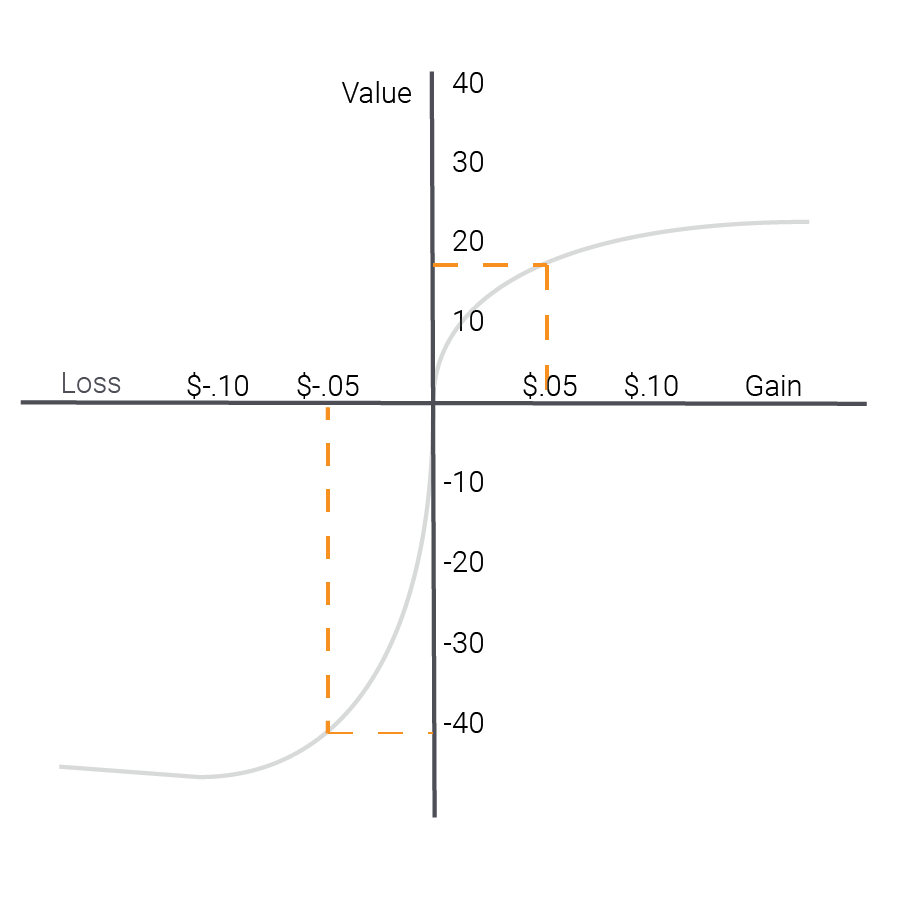

Psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman ran this experiment to test Prospect Theory. They discovered that humans experience gains and losses subjectively, and the pain from a loss is more than twice as powerful as the pleasure of a gain. The chart below shows the relationship between objective gains and losses on the x-axis and our subjective experience on the y-axis.

How to use loss aversion:

Gains and losses are not absolute. Whether we perceive something as a gain or a loss depends on how it is presented (framed) and, specifically, what we use as a reference (anchor) for comparison. So, most gains can be reframed as a loss, and vice versa.

If a gas station offers a regular price for credit and a discount for cash, you’ll perceive the cash price as a gain and the credit price as normal. If it offers a regular price for cash and a higher charge for credit, you’ll view the cash price as normal and the credit price as a loss—even though the cash and credit prices remain the same in both scenarios.

Almost every gain scenario can be reframed as loss avoidance—multiplying its impact by 2X.

Gain: Save money on your electric bill.

Loss: Stop wasting money on energy.

Gain: Learn to manage your chronic disease.

Loss: Get your life back.

When Bose® introduced its Wave® radio with print ads, touting it as “New” (a gain frame), sales were slow. But, when Bose revised the ad’s headline to a loss frame, “Hear What You’ve Been Missing,” sales took off.

The takeaway:

Loss aversion is a powerful and widespread bias, so make it work for you by rethinking how you frame your messaging. “Here’s what you’re missing” can be more than twice as effective as “Here’s what you need” for motivating your audience to change their behavior.

About the author:

This Bias Brief was written by Greg Stielstra, the Senior Director of Behavioral Science at Lirio. Greg is a behavior change expert and published author with over 25 years of experience in marketing and engagement.

References:

Other readers viewed:

Social Proof – Lirio Bias Brief