During the last two decades, breast cancer rates have been decreasing in the United States (1, 2). Certain risk factors, however, have increased (e.g., older average age at first pregnancy, less breastfeeding, more alcohol consumption, higher rates of overweight, and engaging in less physical activity) (3). Nearly one in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some time during their lives (4).

But the risk of breast cancer is not evenly distributed. For example, African American compared to Caucasian women, and elderly compared to younger women, experience greater breast cancer mortality. One tool in the proverbial toolbox for promoting health equity in mammography is Precision Nudging – the application of artificial intelligence and behavioral science to hyper-personalize digital health interventions in the right channel at the right time with the right message for each individual. The behavioral design process undertaken in the development of Precision Nudging interventions mindfully includes social, economic, educational, and cultural barriers to obtaining mammograms.

We acknowledge that true equity in outcomes requires personalization down to the individual level, based on need. For the purposes of understanding how our Precision Nudging interventions perform, however, it is helpful to aggregate data and explore demographic dimensions such as age and race. Specifically for mammography, age and race are two demographics that historically have been related to unequal health outcomes.

Age and breast cancer risk

Although elderly women have the highest risk of breast cancer, elderly women are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from breast cancer. Nevertheless, elderly women do experience greater breast cancer mortality than do younger women. Screening women for breast cancer as they age should remain a priority as the general population in the United States continues to age. According to the American Public Health Association (APHA), adults over age 65 will outnumber children in the United States by 2034.

Race and breast cancer risk

Race plays a complex role in breast cancer risk and mortality. Race disparities in mammography outcomes persist in the United States, highlighting significant inequities in healthcare access and outcomes. Women from certain racial and ethnic minority groups experience higher mortality rates than do Caucasians. For example, African American women have a roughly 4% lower incidence rate of breast cancer than Caucasian women, but a 40% higher breast cancer death rate. Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the African American women.

Age and race and breast cancer risk

Age and race intersect to create unique challenges and disparities in breast cancer outcomes. Women who are both older and belong to a racial minority face an elevated risk of breast cancer mortality compared to other demographic groups. Older age is a known risk factor for breast cancer. Additionally, racial minority women often experience disparities in healthcare access, utilization, and quality, which can further contribute to poorer outcomes.

Exploring Precision Nudging mammography outcomes across age and race

Mammography detects cancer in earlier stages, helping to reduce overall costs of breast cancer treatment in the population and decrease breast cancer mortality (5, 6). For example, women over 40 that have a mammogram every one-two years show a 40% overall reduction in breast cancer mortality (7). Mammography is considered the top 19th most cost-effective clinical preventive services.

We are interested in establishing whether the outcomes of engaging with the mammography messages and obtaining mammograms are broadly equal, suggesting that Precision Nudging for mammography could help promote health equity. Here we explore the outcomes across three implementations of Precision Nudging for mammography in U.S. health systems from August 2020 to July 2023. More than 235,000 women were reached with Precision Nudging messages encouraging them to schedule and attend mammograms they were due or overdue for.

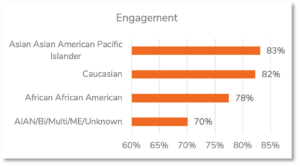

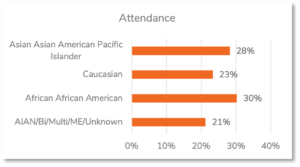

In general, the level of engagement with the mammography messages ranged from 78% for Africans and African Americans to 82% for Caucasians to 83% for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Despite showing lower levels of engagement with the mammography messages, Africans and African Americans showed higher levels of obtaining mammograms (30%) than did Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (28%) and Caucasians (23%). We do not make conclusions about the heterogenous group American Indian Alaskan Native, Bi- or Multi-racial, Middle Eastern, and Unknown due to its diversity.

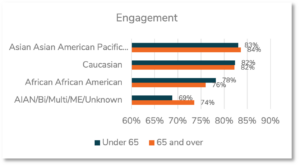

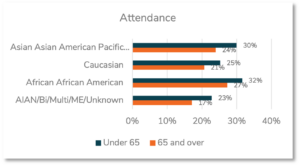

Embracing the dual lens for age and race, we see that age has a larger impact on obtaining mammograms than it does on the engagement with mammogram messages. Overall, women aged 65 and older showed similar levels of engagement to women aged under 65 (81.5% vs. 81.7%), but fewer obtained mammograms (21.0% vs. 25.8%). The largest age by race impact for engagement was seen among African Americans, where those aged 65 and older engaged less than those aged under 65 (76% vs. 78%).

For obtaining mammograms, there were age by race impacts for all the demographic groups: those aged 65 and older attended less than those aged under 65 among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (24% vs. 30%), Caucasians (21% vs. 25%), and Africans and African Americans (27% vs. 32%). Again, we do not make conclusions about the heterogenous group American Indian Alaskan Native, Bi- or Multi-racial, Middle Eastern, and Unknown due to its diversity.

Large demographics categories hide incredible diversity

“AAPI” is an umbrella term that includes over 100 languages and nearly 50 ethnic groups from East and Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Pacific Islands. The term AAPI has continuously changed and shifted to accommodate and respect various identities, from the first use of “Asian American” by student activists in 1968 (which at the time was a much-needed improvement on the term used at the time). Recognizing that a term designed to encompass such a large cultural group has its limitations, we explore the diversity in target behaviors across women’s self-reported countries of origin.1

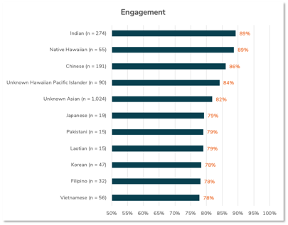

We find that the level of engagement with the digital health messages range from 78% among Vietnamese women to 89% among Indian women.

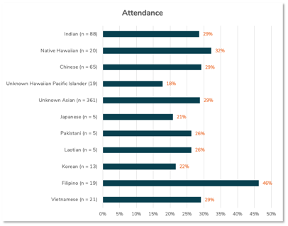

We find that the level of obtaining mammograms range from 18% among women of unknown Hawaiian or Pacific Island descent to 46% among Filipino women.

We need to note that the sample sizes from some countries of origin are small (i.e., n = 5). These conclusions therefore are likely to change as we collect more data and those small groups grow in size. Nevertheless, this snapshot in time is an interesting analysis – and important reminder – of the incredible diversity in behavior that gets averaged out in large demographics categories.

Promoting health equity in mammography adherence is crucial for ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their background or socioeconomic status, have equal access to and benefit from breast cancer screening. By addressing barriers to access, providing culturally sensitive outreach, and delivering tailored interventions, we can reduce disparities and improve breast cancer detection and survival rates for all. Breast cancer continues to impact the lives of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters, wives, and daughters – and fathers, grandfathers, brothers, husbands, and sons.2

References

- Ma J, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics: Recent trends. In: Ahmad A, editor. Breast cancer metastasis and drug resistance: Springer; 2013.

- Zahnd WE, James AS, Jenkins WD, Izadi SR, Fogleman AJ, Steward DE, et al. Rural–urban differences in cancer incidence and trends in the United States. AACR; 2018.

- Sankaranarayanan R, Boffetta P. Research on cancer prevention, detection and management in low- and medium-income countries. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(10):1935-43.

- American Cancer Society. How common is breast cancer? 2020 [Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html.

- Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, Warren JL, Topor M, Meekins A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630-41.

- Moger TA, Bjornelv GM, Aas E. Expected 10-year treatment cost of breast cancer detected within and outside a public screening program in Norway. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(6):745-54.

- Seely JM, Alhassan T. Screening for breast cancer in 2018-what should we be doing today? Curr Oncol. 2018;25(Suppl 1):S115-S24.

Footnotes

1 Several countries of origin had too few observed counts (n < 5) for the Attended target behavior to be included: Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian, Chamorro, Guamanian, Indonesian, Nepalese, Polynesian, Saipanese, Sri Lankan, Tahitian, Taiwanese, Thai, Tokelauan, Tongan, and Yapese.

2 While breast cancer occurs most frequently in women, men get breast cancer too. Due to limited data on men with breast cancer in our population, our study of mammography outcomes across race and age is limited to the study of women.