An in-depth analysis of replies to COVID-19 vaccination outreach reveals thanks, angst — and much more.

Vaccination against COVID-19 is associated with reductions in hospitalization and death rates. In fact, COVID-19 vaccination quickly became one of the most pressing public health goals of the pandemic. Despite myriad approaches to drive vaccination uptake, the initial success of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns was limited and unevenly distributed.

Enter Precision Nudging™.

Precision Nudging uses a type of artificial intelligence (AI) called behavioral reinforcement learning (BRL). The BRL chooses message components from a library of behavioral science content specifically crafted to address the barriers that have been identified in research as reasons why people may delay or avoid health behaviors. The BRL also selects the best timing for each patient, the channel (e.g., email or SMS), and prioritizes the next best health behavior (channel priority).

A SUMMARY OF PATIENT RESPONSES & REACTIONS

- Replied that they had already received a COVID-19 vaccination

- Said they would not get vaccinated

- Sent replies like “thank you” and “❤”

- Replied that they were not the intended recipient

- Autoreplies or unintelligible content

For many people, 2020 was an emotionally and physically difficult year. One behavioral determinant to COVID-19 vaccinations once they were available to the general public in early 2021 involved mental capacity and resilience due to the many stressful events surrounding the pandemic. For this determinant, the BRL compiled messages that embodied the behavioral science strategy Focus on Past Success. Recipients were reminded that getting vaccinated would help them stay healthy and resilient, with messaging around “no matter what the next year would bring.”

By early 2021, when the COVID-19 Precision Nudging vaccination intervention was launched, most adults knew that a vaccine was available. However, it was rolled out in stages based on criteria including vulnerability to infection and front-line worker status, which created confusion for some people not knowing when it would be their turn. The behavioral determinant involving when the vaccine would be available to them kept some people from seeking the COVID-19 vaccine. For this determinant, the BRL compiled messages that embodied the behavioral science strategy Information about Social and Environmental Consequences. Recipients were informed that “Your COVID-19 vaccine is ready for you.”

By early 2021, when the COVID-19 Precision Nudging vaccination intervention was launched, most adults knew that a vaccine was available. However, it was rolled out in stages based on criteria including vulnerability to infection and front-line worker status, which created confusion for some people not knowing when it would be their turn. The behavioral determinant involving when the vaccine would be available to them kept some people from seeking the COVID-19 vaccine. For this determinant, the BRL compiled messages that embodied the behavioral science strategy Information about Social and Environmental Consequences. Recipients were informed that “Your COVID-19 vaccine is ready for you.”

The opportunity

The Lirio team partnered with a health system in one Southern U.S, state. We messaged – via email and text – more than half a million patients believed to be eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine. Lirio received 17,090 text messages in return from 10,948 of those patients.

In the United States, each state creates and maintains its own vaccination database. These vary in terms of their completness and availability for use in public health interventions. The state where Lirio’s health system partner is located does not make citizen vaccination data available, which explains the large number of replies denoting prior vaccination (31.1%).

Our takeaway? The fact that a third of intervention recipients replied that they had already received vaccines elsewhere speaks to the need for consolidated behavioral data in public health emergencies to guide successful interventions. Although it would have been ideal to include only unvaccinated people in intervention outreach, the decentralized nature of data on COVID-19 vaccination in the United States made it difficult to operationalize eligibility criteria. Given incomplete vaccination data, the team erred on the side of including the potentially including vaccinated patients, rather than accidentally excluding the unvaccinated.

Lirio’s findings that 12.7% of replies to the intervention indicated a decision not to vaccinate was consistent with a pre-End User License Agreement (pre-EULA) survey finding an approximate 10% rate of anticipated refusal . Surprisingly, only 4.3% of responses in our sample endorsed mis- or disinformation regarding COVID-19 and vaccination, whereas some studies indicate closer to 50% endorsement of COVID-related mis- or disinformation.

The outcomes

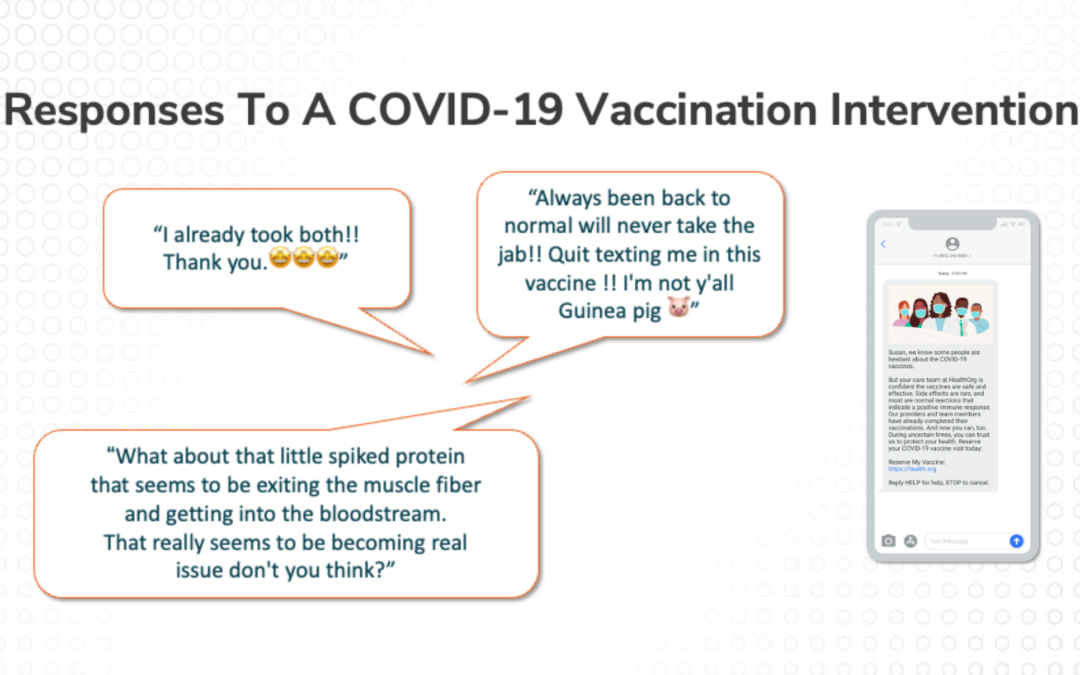

The Lirio team used qualitative descriptive analysis to understand 17,090 unsolicited text message replies we got to our COVID-19 vaccination digital health intervention. What did people tell us when we didn’t ask them to tell us anything?

For the most part, that they already were vaccinated (31.1%), which was encouraging. Another reply type was people who wanted to unsubscribe (a common text response in this population was “stop”). By monitoring the unsubscribe requests, Lirio enhanced the Precision Nudging platform to recognize attempts to unsubscribe via an intent model and suppress messaging, diminishing patient frustration. Another 18.3% sent what were considered benign replies, like “thank you” and “❤.”

The 12.7% who replied that they wouldn’t get vaccinated ranged from polite decliners to the indignant. Their replies provide rich insights into people’s reasons for not receiving COVID-19 vaccination that can inform both future iterations of Precision Nudging interventions as well as other interventions focused on motivating vaccination.

Read More

For the full research report findings of Lirio’s “Responses to a COVID-19 Vaccination Intervention: Qualitative Analysis of 17K Unsolicited SMS Replies,” click here.

Perspective on how age, race, and outreach contribute to vaccination propensity

A heartening discovery was that about a third of the text messages were letting the health system know the recipient had already been vaccinated elsewhere. Many of these texters expressed gratitude that they’d been offered a vaccination. Another third were typos, auto-responses, and wrong numbers. The remaining third were varieties of “no thank you” ranging from polite to the not-so-polite.

We also evaluated whether response types were sent proportionally to different groups’ representations in the patient population. The Lirio team found that older and African American patients were more likely to respond that they’d already been vaccinated than suggested by their base rate in the population, while younger and white people were more likely to share negative responses than expected from base rates. We speculate that early campaigns to get older adults vaccinated were effective in shaping positive receptions, while racial disparities in vaccination rates likely owe much to structural inequities and access limitations. These findings speak to the need for a continued focus on health equity and how different communities may experience the same health behaviors differently, requiring personalized support.

E. Susanne Blazek, Ph.D., also contributed to this research.