Host: Greg Stielstra (GS), Senior Director of Behavioral Science at Lirio

Summary: Lirio Sr. Director of Behavioral Science Greg Stielstra walks listeners through a preview of The Whole Mind Webinar series, in which he discusses dual process theory, Systems 1 and 2, relevant cognitive biases, and more. Listen to learn how engaging the whole mind gives communicators our best shot of driving behavior change.

Greg Stilestra:

Hi and welcome to The Behavior Change Podcast by Lirio, the program where we explore the marvels of behavioral science and ways of applying it to make a better world. I’m your host Greg Stielstra.

On today’s show, we’ll listen in on a recent Lirio webinar, one that explored what I call “whole mind” behavior change. It begins with a look at dual process theory, the two ways we humans think and decide. Then it surveys a collection of cognitive biases that influence our subconscious decision-making process, and ways that we can use them to change behavior. But as always, we’ll begin with a Bias Brief.

Temporal Landmarks

Why do we make New Year’s resolutions? Why not resolve to start a new diet on February 2nd or quit smoking on some Tuesday in August? We could, but we shouldn’t. Not if we want to succeed. The date we begin pursuing a new goal can influence whether we achieve it at all. Dates like January 1st, a significant anniversary, the first of the month, or the first day of a work week represent temporal landmarks, and they possess special power.

Research has shown temporal landmarks increase our likelihood to pursue a goal and may even help us accomplish them by changing the way we see ourselves.

Temporal landmarks stand out as dividers that separate people’s past, current, and future selves, weakening the psychological connection between these temporal selves. That’s according to researchers at the Warden School.

These fresh starts are associated with increases in aspirational behavior, free from the foibles and limitations of our past self, our future self, the one that’s waiting just beyond that temporal landmark, is capable of so much more.

We believe we can accomplish something new because we believe we are someone new. Researchers think the belief that our future self is superior to our past self enhances our self-efficacy, our belief in our ability to accomplish some goal. And those who believe often achieve. Higher self-efficacy has been shown to increase persistence at a task, and persistence is correlated with achievement.

Loss aversion may also play a role. Prior to the temporal landmark, our lives had been littered with failures, one more will do little to change this. But temporal landmarks wipe the slate clean, ushering in a new era unblemished by failure. Eager to preserve our new, perfect record, we work harder at achieving our goals.

Finally, temporal landmarks influence when we prefer to receive benefits or incur costs. We prefer benefits to occur before temporal landmarks where we perceive them as benefiting our present self. However, we prefer cost to occur after temporal landmarks where our future self must pick up the tab.

Whether you’re trying to help people save for retirement, stop smoking, or participate in an energy conservation program. Carefully choosing the start date can improve their and your chances for success.

Here are some application ideas: Start registration campaigns after a temporal landmark. Offer rewards like bonuses or context prizes before temporal boundaries, like the end of the year, to increase their perceived value. Position activities perceived as cost like increased 401(k) contributions to occur after temporal boundaries, like the end of the year, to minimize their perceived impact.

Use temporal landmarks to increase medical appointment adherence. Encourage people to schedule uncomfortable procedures like colonoscopies or Pap smears beyond a temporal boundary. For example, ask women during the 2019 calendar year to schedule the pap smear for the 2020 calendar year. Their current self will schedule the appointment that their future self must keep.

The Whole Mind Webinar

Hi and welcome to The Whole Mind Webinar series, where we explore the science of human decision-making. I’m Greg Stielstra, Senior Director of Behavioral Science at Lirio.

I want to start our exploration of human decision-making by telling you a personal story. I laid in bed one morning contemplating whether to get up or lie there a little bit longer. And when I finally decided to get up, I had a startling realization. One of my feet was already on the floor. I’d began acting on my decision to get out of bed before I became consciously aware I had made that choice.

Now, you might think I’m some sort of freak, and you wouldn’t be wrong, but it turns out we all do this. Studies using FMRI machines have revealed that people make a decision about seven seconds before they become consciously aware of it. Let me say that again, we make a decision about seven seconds before we become consciously aware of it.

Now, we tend to think our decisions are entirely conscious. But this illustrates the powerful role that our subconscious plays in our decision-making process and why any effective behavior change intervention has to include the whole mind, both our conscious and our subconscious decision-making processes.

So, let’s take a closer look at each process, its defining characteristics, and how to go about influencing each of them.

Dual Process Theory

Dual process theory describes two different mechanisms we use for making decisions. The first I’ll describe is called System 2. Catchy name, I know.

The System 2 is our conscious thought process. It is slow, because it is sequential. That is, we can attend to only one problem at a time. It’s also deliberate. We consciously decide to apply it. It’s effortful, the brain uses a disproportionate amount of the body’s total energy, and System 2 is especially gluttonous. And it is rational. It tends to consider only relevant information when making its decisions.

We use System 2 when we solve a multiplication problem, like 17 times 24. Now, we may not immediately know the answer, but we know we can solve it. We apply ourselves to the problem, solving various parts of that equation, holding certain numbers in our working memory, and moving sequentially through the process until we arrive at the answer. Slow, deliberate, effortful, and rational.

Now, System 1 is very different. It’s unconscious. We aren’t aware of its operation. It’s fast because it uses a parallel process that can work on many problems simultaneously. And it’s automatic. We can’t prevent it from happening. System one assesses every situation we encounter and renders a decision or suggestion about what to do, whether we like it or not. And it is effortless, or at least it feels that way. We don’t tire of using System 1 the way we tire of using System 2. We do it all day every day without breaking a sweat.

Unlike System 2, System 1 relies on past experience, contextual cues, and mental shortcuts called heuristics to make its decision. System one allows us to understand someone’s mood by their facial expression, in an instant and without trying. Boom. Unconscious, fast, automatic, and effortless.

And though these systems are separate, they are far from equal. By some estimates, our brains process 10 million bits of information every single second subconsciously using System 1. But we can process just 50 bits per second consciously using System 2. Working memory, that cognitive system responsible for temporarily holding information available for processing by System 2, is so limited that most people can only hold about seven numbers or six letters or five words in it at any given time.

Think about that, of the 10 million bits of information our brains process every second, only 50 bits are devoted to deliberate, conscious thought—just about 0.0005%.

So the truth is, we’re not built to be ever vigilant. Instead, we are wired to avoid continuous conscious decision-making.

Now, most of the time, System 1 runs automatically and System 2 is just chilling in the background. Because System 1 is automatic and fast, it’s the first to render a decision about the things we encounter. When System 2 agrees with a suggestion, impressions get turned into beliefs and things run pretty smoothly.

If System 1 runs into trouble, encountering something unfamiliar, disfluent, or difficult, System 2 comes online to help. As a result, some scientists estimate we make about 95% of our daily decisions using our subconscious System 1 and only about 5% using our conscious System 2.

By now, you can probably understand why behavior change efforts are more successful when System 1 and System 2 agree—when you’ve engaged the whole mind. Well for that to occur, you have to understand how to influence both processes.

Now, not only do these two processes operate differently, we influence them differently too. We influence System 2 by providing information hoping to change someone’s mind, so they will then change their behavior. If I wanted you to wear a safety belt when driving your car for example, then I might show you statistics demonstrating that people who wear seat belts are more likely to survive a crash. I’d hope that you’d see the sense in my argument and decide to begin wearing yours.

This is how most behavior change efforts are designed, as information campaigns. To work, they must attract your attention, get you to read and understand all of the statistics, draw the appropriate conclusion, and then consciously act on it going forward every single time. It can be done, but it requires near constant effort, and that is difficult to sustain. It explains why most efforts like this work a little.

What if you could change your impulse by influencing System 1?

Well, you can. Influencing System 1 requires a different approach. Here we must alter the context to change the behavior directly and people change their mind last.

If I want to influence your System 1 to have you wear your seat belt, I might install a buzzer in your car that sounded until you put it on. That buzzer does not require you to make a rational judgment, it’s an environmental cue the has nothing to do with the safety benefits of seat belts, but everything to do with getting you to wear one.

Now, we may think that we use conscious System 2 to make rational choices. In reality, we make most decisions with System 1 and use System 2 to rationalize, justify, and explain a way the System 1 decision we already made. Most of the time, your System 2 is simply making up fancy explanations for why your foot is already on the floor.

Now, I’m not going to waste our time discussing how to influence System 2, it impacts just 5% of our decisions, and you already know how to build information campaigns. You’ve been doing it for years.

Instead, let’s talk about how to influence the system responsible for 95% of our choices, System 1. The same factor that makes System 1 so efficient, so fast, also makes it irrational. It’s called heuristics.

Heuristics are rules of thumb or mental shortcuts that System 1 uses to form judgments and make decisions. Those shortcuts often lead to cognitive biases. These are systematic deviations from normal judgment that affect our decisions. Behavioral scientists have identified more than 150 of them. By understanding what they are and how they operate, we can use them to nudge people toward behavior change by designing interventions that alter their impulses.

Cognitive Biases

Let’s take a quick look at a few cognitive biases and how they affect our judgment, and also we can apply them to behavior change interventions.

Messenger

It’s irrational, but people’s response to a message is influenced by who delivers it. Several universities have conducted experiments where they tried to get pedestrians to cross the street against the light. A man or a woman would approach a crowded intersection, wait till the traffic cleared, say to those around them, “It’s clear, we can go.” And then begin to walk across the street while researchers record how many people they convince to follow.

Some of time they were dressed casually, other times they were dressed formally. Now, which outfit do you think made them more influential? Yep, more people took this jay walking advice when it came from someone who was formally dressed. But would you have guessed that the difference was 350%?

Wow, the trappings of authority. Formal attire compared to casual attire gave complete strangers confidence in an individual they had not met before.

What messengers should you use?

Well, the most influential messengers have authority in a related area. If your question is what’s wrong with me? Then your doctor has authority. If your question is what’s wrong with my car, then your mechanic has authority.

We also prefer messengers with similarity. The more we perceive a messenger as being like us, the more likely we are to believe their message or comply with their request. That’s why reader reviews on Amazon are influential. We assume that Betty from Poughkeepsie is like us.

And a messenger must be likable. In fact, if we don’t like a messenger, it robs them of their authority.

Finally, remember that every message has a messenger. Even if you don’t assign one, the message’s recipient will. So, it’s better for you to assign an authoritative, similar, likable messenger than to let your user assign their own, because the one they assign may be less influential.

Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics as a psychologist for work he did with Amos Tversky. They found that people feel the pain of a loss more than twice as much as they enjoy the benefit of an equivalent gain. And significantly, they discovered that whether we perceive something as a gain or a loss depends on the reference point or anchor to which it is compared. In other words, gains and losses are subjective and they depend on the reference.

A study of Olympic medal winners found that, judged by their facial expressions, gold medal winners appeared the happiest, no surprise. But they were followed by bronze medal winners and finally silver medal winners. So, why weren’t third place bronze medal winners also third happiest? The anchor.

Researchers found the bronze medal winners compared their achievement to the alternative of not winning a medal at all. And that anchor made them see their medal as a major accomplishment, which made them happy.

The silver medal winners by contrast tended to compare their achievement to the gold medal. Instead of thinking of themselves as winning the silver or beating the bronze, they tended to view themselves as losing the gold. And that made them less happy.

Almost any offer can be framed as either a gain or a loss. Bose introduced its Wave® radio with a major print ad campaign that touted the radio as “NEW.” This created a gain scenario, where consumers could gain something new by purchasing the radio. Sales struggled.

After working with Dr. Robert Cialdini, a behavioral scientist at Arizona State, Bose changed the headline to: “Hear what you’ve been missing.” This created a loss scenario which was more motivational, and sales increased by 46%.

Another experiment by Dr. Cialdini illustrates the power of contrast influence choice. Cialdini asked a number of people whether they could chaperone a troubled teen on a day trip to the zoo. And only 17% agreed. It didn’t sound like a fun way to spend a Saturday. But for the other half of the people in the experiment, he altered the request.

He said, “Will you mentor a troubled teen weekly for two years?” That was a huge request and almost everyone said no. “Okay,” he said, “I realized that’s a big request. Would you at least, then, take them on a day trip to the zoo?” This time 76% said yes. Presenting a larger request first, two years of mentoring, made the actual request, a day trip to the zoo, seem smaller and reasonable by contrast.

You can leverage loss aversion by talking about what your prospects will lose by not buying rather than what they’ll gain from buying.

Behavior change agents can use loss aversion to nudge people to conserve energy for example or improve their health. Instead of saying, “Save money by switching to LED light bulbs,” a gain scenario, it may be more effective to say, “Stop wasting money with incandescent light bulbs—switch to LEDs.” The beauty of this technique is that it is almost always available by simply rephrasing or reframing your offer.

Use contrast when possible by presenting the largest or most expensive alternative first. For example, if you want people to install weather stripping around leaky windows, you can begin by asking people to replace their old drafty windows. But that’s an expensive and difficult task. Ask them then if they would at least seal them better with weather stripping and I’ll bet they’ll comply.

We are strongly influenced by others. The more uncertain the situation, the more likely we are to copy other people’s behavior rather than trying to figure it out for ourselves. Trends occur when lots people copy others’ decisions, rather than making independent choices.

Social norms can be used to encourage desired behavior, but be warned: they are a double-edged sword. People also copy bad behaviors. If you want people to lose weight pointing out that 60% of the population is overweight may backfire, convincing people that obesity is acceptable rather than convincing them to avoid it.

Leveraging social proof can be as simple as making people’s choices visible. Apple was a late entrant to the MP3 player market and had some catching up to do. It realized that the players were small, could likely be hidden in people’s pockets, backpacks, or purses. The earbuds and cables, however, would be visible. Since all other manufacturers made their cables black, Apple decided to make its white. This made it immediately apparent when someone was using an Apple product and made their decision available to be copied.

In another experiment, researchers tried to convince hotel guests to reuse their towels using different appeals. The first appeal said the hotel would make a donation to an environmental organization if you reused your towel. That appeal convinced 38% to participate. The second appeal said the hotel had already donated to the environmental cause and asked the guests to do their part by reusing their towel. That appeal convinced 48% to participate.

The third appeal leveraged social proof by saying 75% of hotel guests chose to participate, you should join them. This approach convinced 53% to participate. However, researchers improved participation an additional 11% when they changed the appeal to read: 75% of people who previously stayed in this room chose to participate.

People imagine that others who previously stayed in the same room must have more in common with them. And that similarity made their choice more influential. Irrational? You bet. But also powerfully persuasive.

But as I mentioned, social proof is a double-edged sword. When the Petrified Forest National Park had a problem with people stealing artifacts from the park, it posted [a sign like this]:

By making new visitors aware that stealing rocks was a common practice, they inadvertently established it as a social norm that encouraged copy-cat behavior, and theft increased by a factor of three.

To leverage social proof, make the desired choice visible so people can see it and copy it. Especially when it’s chosen by similar others. Make undesired choices invisible. For example, if you want to reduce obesity, don’t talk about how obesity is on the rise. That only establishes it as a social norm.

Default Bias

Default bias describes our tendency to go with the flow of preset options. System one is likely to accept the default. Bringing System 2 online is hard work and so we avoid it. And this means that we’re likely to accept default settings and move on, even for serious choices.

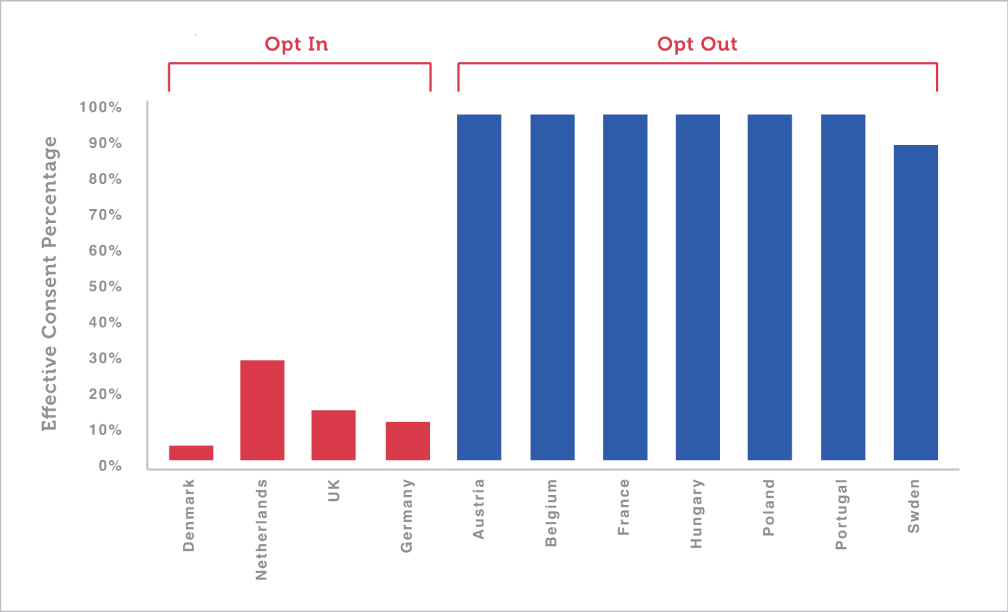

On the left side of [the image above] is a chart showing nations that ask people to opt in to organ donations. They get about a 10% participation rate. The Netherlands, however, is slightly higher at 28%. But it spent millions on national radio and TV ad campaigns and direct mail to every citizen in the country.

Meanwhile, right next door, the Belgians changed which box was already checked on the form and got a 90% response rate. So, on the right-hand side of the [image above] are countries where organ donation is opt out—they assume you’re in unless you check a box to opt out. They get a 90% response rate.

The choices are the same, organ donation, yes or no. But the results are shockingly different. If you must opt in, then doing nothing results in non-participation. If you must opt out, then doing nothing results in participation. When the easiest path leads to participation, people will do almost anything—including donating their organs.

I worked a company called Health Ways that redesigned its call center and added work stations that could be adjusted to a stand–up or sit–down height. And quite by accident, they were installed at various heights—some stand–up, others sit–down. So, when we let people back to their desks, guess what happened?

Yep, they kept the default setting. If the station was set to a stand–up height, they stood. If it was set to a sit–down height, they sat. There were no exceptions. People accepted the default setting 100% of the time.

By making the desired choice the default, more people will make that choice. This doesn’t limit their options in any way, they could still choose “No”—but they don’t. Applying default bias is easy. Whenever possible, make the desired choice the default. When that’s not possible, use something called active choice. Active choice means there is no default and users must indicate a selection. This creates equal friction for all choices and is more likely to engage someone’s System 2, getting them to think hard about it and select their preferred choice.

Goal Gradient

Goal gradient describes our tendency for our efforts to increase as we approach a goal. Scientists noticed that rats moving through a maze picked up speed as they got closer to the cheese and wondered if this would also be true for humans—and it is. In an experiment with frequent customer cards, they proved it.

One group of people was given cards with 10 circles and told that after buying 10 cups of coffee, their 11th cup would be free. But a second group was given cards with 12 circles and told after buying 12 cups, the 13th was free. But then the clerk punched two circles as a bonus. This made the math for both cards the same, but they felt different.

Consumers with 12 circle cards felt as if they had made more progress toward the goal and people with this card completed it 19% faster.

Here’s an idea from Rory Sutherland, vice chairman of Ogilvy in the United Kingdom. He thinks goal gradient can help people complete a course of antibiotics instead of quitting when they begin feeling better. Rather than giving people 24 red pills and telling them to take them all, Sutherland suggests you’ll have more success if you give them 18 red pills and six blue ones, then tell people to take all the red pills, and then take all the blue pills.

Mentally, people see these as two different tasks. One, take the red pills, and two, take the blue pills. Goal gradient means they are closer to the end of each task and more likely to complete it.

Here’s how you can apply goal gradient to marketing: Help people see their progress toward the goal. If they’re taking a survey, show them how many questions remain. You can break longer tasks into chunks as another tactic, give people credit for steps they’ve already taken, and finally use the way you present things to increase perceived process or progress.

Constructed Choice

People tend to think our preferences are fixed, internal, and only influenced by relevant alternatives, that we know what we like and choose it regardless. But actual evidence suggests our preferences are quite dynamic, and we actually construct them at the time of choice based on context.

This is an actual subscription offer made by The Economist magazine. People could get the online subscription for $59. The print-only subscription for $125, or print and online also for $125. This collection of alternatives caused 84% of people to choose print and online for $125, and no one to choose print only.

So, you’d think that by removing the option no one chose, print only, there’d be no effect. Wrong. When they removed the print only option, only 32% of people chose print and online. The first scenario was a value judgment where print and online looked like two formats for $125 was clearly superior to print only, just one format for the same price. Most people ignored the online-only option.

However, when print-only was removed, the choice became a price judgment which online-only easily won. The alternatives and the way they’re presented can have a profound influence on the selections people make.

Here’s some rules to guide you when trying to get people to make your desired choice. Present selection sets that optimize the perceived value of the target item. That’s what The Economist did. Another idea is what I call “good apple, bad apple, orange.” It turns out people are very good at distinguishing a superior apple from an inferior one, but pretty bad at distinguishing the difference between an apple and an orange.

So, create selection sets that include an inferior item, a superior item of the same type, and a wholly different item—the orange.

Finally, create a false target, a high-priced alternative you don’t expect to sell that makes the real item look more attractive. Remember the contrast principle.

Choice Paradox

As the number of alternatives increases, people become less likely to choose at all. If you ask them, people will say they want a larger selection, but that’s their System 2 talking, and it doesn’t know what it’s talking about. In reality, as the number of alternatives increases, people find it harder to decide.

In one experiment, for every 10 new mutual funds added to the list from which people could choose for their 401(k), participation in the retirement program fell by 2%. As they increased the number of choices, choosing the right funds became more difficult and folks gave up, even though they were giving up $5,000 in company matching funds.

Choice can be overwhelming and every time I go to the grocery store, I think if they add one more tube of toothpaste to the aisle, I’m going to stop brushing altogether.

So, what should you do? Well, you can reduce the number of choice alternatives. If that’s not an option for you, try presenting a smaller selection set. A typical Barnes & Noble superstore for example has 110,000 titles on its shelves. That can be pretty overwhelming. So, it displays a smaller selection set in the form of a best sellers list. Not only are there fewer books from which to choose in this section of the store, but each of them benefits from social proof because of their popularity.

Conclusion

So that’s a quick tour through a handful of cognitive biases. It should help you get started designing whole mind marketing and engagement plans of your own. You can also visit Lirio.co and read our blog or listen to our podcast. If you work in healthcare or energy and want help changing behavior, contact Lirio, we’re here to help.

You’ve been listening to The Behavior Change Podcast by Lirio. Lirio provides an email-based behavioral engagement solution that uses machine learning, persona-based messaging, and behavioral science to help organizations motivate the people they serve to achieve better outcomes. On the web at Lirio.co, L-I-R-I-O.C-O, or follow us on Twitter @Lirio_LLC.

Ready to Turn Your Knowledge into Action?

The thoughts and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the person speaking. The opinions expressed are as of the date of this podcast and may change as subsequent conditions vary. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this podcast is at the sole discretion of the listener.

© Lirio, LLC